The unbelievable trajectory of Danny Boyle's 'Slumdog Millionaire' in the universe of film awards has aroused endorsement and loathing for the film in equal measure. Poverty porn/hymn to hope; slum tourism/no-bull honesty; cliché-ridden bilge/heart-warming tribute - contending adjectives multiply with every review.

The film is all of this, of course, but it manages to replace - at least for yet another fleeting cinematic moment - the power towers of Manhattan and Nariman Point with Dharavi's quilted rooftops. Map this enormous waste land of three square kilometres fringed by mountain peaks of rubbish, home to more than a million people, and you get the universe where the other half lives, eats, defecates, melds into succeeding generations amidst constant and imminent dangers, ranging from chronic diarrhoea to thriving networks of girl child traffickers.

In the film, Salim, protagonist Jamal's elder brother, proclaims in his moment of triumph, " India is at the centre of the world and I am at the centre of this centre." He could just as well be speaking for Dharavi, which wears lightly the sobriquet of being Asia 's largest slum, and which is supposedly the setting of the film. Dharavi, having long outgrown the fetid drained-out mangrove swamp that had once given it birth, has now come to be the core of Mumbai, as the city grew amoeba-like to encapsulate it. Mumbai, remember, is the capital city of the state of Maharashtra, which has a per capita that is more than 40 per cent higher than the all-India average. But the state also has the gravest intra-state disparities among all Indian states, and the largest slum-dwelling population.

These concentric circles of immense wealth and abject poverty could well provide us with a glimpse of India in the year 2050, when 55 per cent of its population (an estimated 900 million) is projected to be urban-based and where the disparities and inequalities of the country could be replicated in mega-slums slicing through monster megapolises.

Like in most cities of the world, those who controlled Mumbai regarded new settlers with ambivalence: they needed their labour but made little provision for their well-being. In his essay, 'Migration and Urban Identity: Bombay's Famine Refugees in the Nineteenth Century', social historian Jim Masselos quotes a Government of Bombay note of 1889 that complained, "Bombay is becoming more and more subject to an influx from Native States of paupers, helpless, troublesome and diseased persons." A report from the 'Bombay Gazette' of the same year grumbled that these people lie "huddled together like sheep and (are) breeding disease."

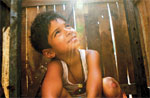

These faceless women and men were the forebears of Salim, Jamal and Latika, the child protagonists of 'Slumdog Millionaire', discarded children growing up on forgotten peripheries. Perhaps nothing underlined the separations between them and the more privileged city dwellers than their close proximity to human waste. The scene that arguably had the highest cringe value in the film shows a young Jamal swimming through human faeces in his desperation to get an autograph from the great Amitabh Bachchan, superstar and icon. Covered in the foul odorous substance of the soakpit, he holds up the prized autograph, screaming out, "Amitabh ka autograph mil gaya ! (I've got Amitabh Bachchan's autograph!)" While the scene offended many viewers in India, it also drives home a point made by Mike Davis in his book, 'Planet of Slums': "Constant intimacy with other people's waste, is one of the most profound of social divides... living in shit - truly demarcates two existential humanities".

Doyle's Dharavi cinemascape has some striking shots of humongous sewer pipes criss-crossing the bleak rubbish-strewn environs adjoining the slum. Ironically, those pipes carrying Mumbai's waste out of the city centre pass through Dharavi but none of them service the area itself. According to one estimate, dating back to November 2001, Dharavi has only one toilet per 1,440 residents.

This geography of sanitation testifies to a history of civic neglect, first under the British Raj, and later in independent India . Swapna Banerjee-Guha, Mumbai-based geographer, writes about how Mumbai's urban developers replicated the model of the rulers. She writes: "Systematic urban planning in Bombay took a long time to evolve. In the late fifties, when it finally took shape, its link with the business class had already been forged; in later plans this bias became evermore evident." Interest in Dharavi today is driven more by the value of the land on which it is located rather than the welfare of its people.

The saucer-eyed Latika in 'Slumdog Millionaire', who tags along with her Jamal and Salim as part of a ragged threesome in the first half of the film, symbolises innumerable little girls like her who end up being trafficked. A Department of Women and Child Development report notes that 80 per cent of Indian children who are trafficked belong to families dependent on wage labour for survival. In Mumbai, according to National Crime Record Bureau statistics, over 2,000 women and over 4,000 children are reported missing every year, and these are only the reported numbers. For traffickers, dealing with children's "re-usable" bodies is a high profit, low risk venture.

Of course, 'Slumdog Millionaire' is also a fantasy. How does Jamal mutate into that incredible healthy specimen who has all the right answers at a game show? How do Jamal and Latika, two floating fragments in a sea of humanity, get to meet again and fall in love? If this is realism, we will have to term it magic realism. In any case, the story of one Jamal winning 20 million rupees in a game show does not alter the reality of India 's innumerable lost children and lost childhoods. But what the film does do is to touch lightly on many themes that should rightly resonate through a country that misses no opportunity to showcase itself as the new participant at the high table of global dominance.

(Courtesy: Women's Feature Service)

null

|

|

Comments: